Homebody/Kabul

Tangent Productions and Sam Hawker in Association with BSharp at Belvoir Street Theatre Downstairs

Sydney 2008

Christopher Hurrell deftly directs the company of ten in the tiny, tricky Downstairs space and has drawn memorable performances from all. Immensely rewarding, unexpectedly funny, provocative and moving.

STAGE NOISE

Homebody

Gillian Jones

Doctor Qari Shah

George Kanaan

Mullah Aftar Ali Durranni

Keith Agius

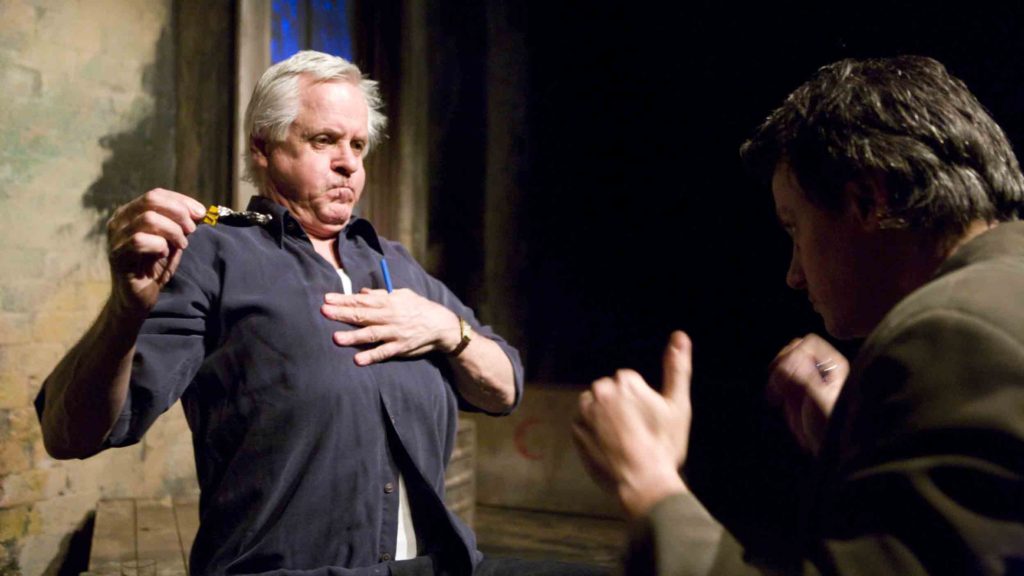

Milton Ceiling

Tony Llewellyn-Jones

Quango Twiselton

Simon Bossell

Priscilla Ceiling

Lotte St Clair

Mahala / Afgan Woman

Odile Le Clezio

The Munkrat / Border Guard

Craig Meneaud

Khwaja Aziz Mondanabosh

Nicholas Papademetriou

Zai Garshi

James Evans

Director

Christopher Hurrell

Set Designer

Tom Bannerman

Costume Designer

Amanda McNamara

Composer / Sound Designer

Rosie Chase

Lighting

Grant Fraser

Assistant Director

Velalien

Dramaturg

Sime Knezevic

Co-writer of Kabul Theme

Nicholas Ng

Producer

Sam Hawker

Associate Producer

Saskia Vromans

”"The playwright of ideas compels us to look afresh at tinderbox issues in a feverish search for understanding the near unsavable world of Homebody/Kabul. It's about desolation and love in land-mined places, private agony and public squalor, fathers and daughters, the Babel of language and lost civilizations, disintegrating, rotting cultures, sordid Western values and furious opposites, murderers and fanatics, opium highs and tranquilized lives lived out in disgust and self-obliteration. It's about travel in the generous, best sense of the word--travel of the exploding, despairing mind and soul. To where? A place where warring people might one day meet, where steps can be relearned and the meaning of words reborn. The voice of yearning within Homebody/Kabul has now become more urgent, as if time were running out in sickness of heart and soul. Name me a better play of our time--for our time."

John HeilpernNew York Observer

DIRECTOR’S NOTE

If you had asked me in 1998 – one year before this play was written – I would have told you that it was impossible that my generation would look back in ten years and ask, bewildered; “How did the world get so bad so quickly?” It seemed to me at my 21st birthday that I was blessed, born at the time when world war, cold war and empire were a thing of the past, and when we were already on the slow but inexorable up-swing to ever-spreading peace, ever-spreading compassion, ever-spreading wisdom and ever-spreading liberalism. I was a bit like Louis, in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, naively convinced of the world’s eventual perfectibility, like Louis, my disappointment lay not in the world but only in my own emerging failure to live up to such a vision of perfection.

Naïve indeed.

As the horror – of how easily, quickly and dramatically the world can reveal itself to be on a much more grim course – unfolded, I have looked to prophets of the theatre, armed with vision much clearer than my own, to attempt to answer the question I never thought I would have to ask.

Tony Kushner is truly a prophet of the theatre. In 1991, he forged his experience of the horror of the AIDS epidemic in the 80’s into “Angels in America”: a testament that looked forward to the optimism and sense of impending triumph of the 90’s – “Millenium Approaches!” declares the Angel in rapture. Y2k was not an apocalypse to be feared, merely a challenge to meet and a threshold to cross into a golden new century that would surely contain the culmination of our dreams.

In 1999, before the new millennium had even dawned, Kushner peered into the largely ignored trauma of Taliban ruled Afghanistan: it was, as the Homebody points out, merely the latest in a long long history of trauma: and there he saw an irresistible trap made by the West and waiting to claim the West as its victim.

In the dangerous collision of cultures, we find a suspenseful, intriguing and raw drama that foresaw much of the horror associated with the disastrous situation in modern-day Afghanistan.

A British, book-obsessed housewife bides her time with a guidebook of Kabul. She reaches the Taliban-ruled city in August of 1998, before disappearing under mysterious circumstances. As her husband and daughter search for her and the answers to her disappearance, they discover a chaotic world where the political and the personal becomes blurred and increasingly ambiguous.

This play drew particular attention after September 11 because it appears to predict the attacks in the moment when the abused Afghan librarian, Mahala, cries out:

“You love the Taliban so much, bring them to New York! Well, don’t worry, they’re coming to New York! Americans!”

But I think its true relationship to this recent dark age is that it dares to suggest the possible antidote. It is our old certainties that confine us to violence and conflict; be they religious, cultural, material or political. Uncertainty terrifies us. “Uncertainty kills” says Priscilla at the end of the play. To which Mahala counters “As does certainty”. Uncertainty kills only if we fail to come to terms with it, the challenge is to learn to live in the tension between my view of the world and yours, knowing that neither is wrong and neither right. Certainty kills for certain. Or rather the fight for it does.

Homebody/Kabul does not, can not, answer the unanswerable, but it searches for answers with wisdom, compassion, and breath-taking poetic beauty.

“IF Tony Kushner had never written another word for the stage after Angels in America his place in American - and world - theatre would have been assured. As it is, Homebody/Kabul, his prescient (aka common sense) play from 2001 has finally reached Sydney thanks to independent producers Sam Hawker & Tangent Productions under the wing of B Sharp at Belvoir St.

As he did with the love-in-the-age-of-AIDS epic, Kushner makes the personal political and the political excruciatingly personal. This time the landscape is at once more intimate while encompassing the sweep of history and geography as they pertain to that region we know as Afghanistan and its neighbours.

The play is a curious shape opening with Gillian Jones as the Homebody - a nice, middle class London woman - engaging the audience in a one-sided and non-stop 45 minute one-person conversation. Not a monologue, by the way, it is definitely a conversation, it's just that she's the only one talking. Although she does it with such extraordinary spontanaeity and obsessive, dotty warmth that the night I was in, a woman in the front row began to reply to her questions, so convincing was Jones's engagement with her listeners.

Homebody reads aloud from an out of date guide book to Kabul. She is fascinated by the city and its history and by words and concepts in their wider sense to a point way beyond eccentricity. She describes her state as "psycho panicky" and although you won't find that in Wikipedia, it's pretty much self explanatory. Homebody's mind and ideas float and leap freely from association to association in a dizzying and compelling display of language. Homebody is possibly the best work Gillian Jones has done in a long time; which is not to say that she hasn't done other good work, but rather, that this performance is sublime.

An abrupt change of pace and style is the consequence of Homebody's departure from comfy London to Kabul where she apparently disappears. Her personal, inner quest is immediately followed by an outward but equally personal quest by her husband and daughter as they blunder into Taliban territory to find her in their metaphorical neo-colonial hobnail boots.

Tony Llewellyn Jones is strong as Milton Ceiling (Kushner has fun with "English" names) as he slowly slides from computer engineering certainty to bewilderment and a logical loosening of absolute conviction in the face of loopy experiments with Afghanistan's most famous local product - not carpets. His entree into the world of opium is an expatriate English NGO staffer, Quango Twiselton (Simon Bossell) whose name tells you everything about the rather limp, dissolute yet well meaning chap he is.

As Milton's daughter Priscilla, Lotte St Clair is a painful mixture of boldly independent and a lost lamb as she searches not only for her mother but for the nature and status of their relationship. In Kabul she quickly learns that independence and other western follies are not going to be tolerated. She falls in with - or is picked up by - Khwaja Aziz Mondanabosh, an opportunistic poet and would-be guide to Kabul, played by Nicholas Papademetriou in what is also one of the best performances he's given in some while. And the same must be said of Odile Le Clezio whose portrait of an educated, middle class librarian whose life is in jeopardy at the hands of the Taliban and the mullahs because she is all those things, is also electric.

There are no weak links in the cast: George Kanaan, Keith Agius, Craig Meneaud and James Evans bring implacable hostility and righteousness to their roles as various Afghani clerics and gunmen. It's as if Kushner's script and Gillian Jones' inspired playing of the first part of it are the twin rockets that launch the rest of the play and the actors on an unstoppable upward trajectory.

The play also abounds in ideas and strands that loosely weave and finally tie up as fully fledged concepts. Milton's computers and the librarian's Dewey decimal system are as impenetrable to the uninitiated as Khwaja's misplaced faith in Esperanto - in which he writes his poetry. For the mullah who arrests him, Esperanto is not only impenetrable but subversive - as are the burqas forced upon Priscilla and embraced by the librarian. Frank Sinatra's 13th album for Capitol Records is as bound up in the action as is the Homebody's early musing on the Greco-Bactrian confusion (ancient China in case you're wondering).

Christopher Hurrell deftly directs the company of ten in the tiny, tricky Downstairs space and has drawn memorable performances from all. Set, costumes, lighting and sound/composition by Tom Bannerman, Amanda McNamara, Grant Fraser and Rosie Chase respectively are also very fine.

Homebody/Kabul is a deceptive play. At first it seems broken-backed because of Homebody's 45 minute-solo fireworks. On reflection, however, the character sets up and sets running all the story strands and ideas that the rest of the play and characters then takes up and expands upon. And it makes sense that she should be such an over-arching, if invisible, presence in the second half because without her, there is little sense in pursuing the ghost against such odds.

You may have heard that this is a long play: it is. But it's also immensely rewarding, unexpectedly funny, provocative and moving.”

Diana SimmondsStage Noise