Macbeth

Darlinghurst Theatre

Sydney 2010

In Hurrell’s production, we’re exposed to something in touch with the madnesses that control us, whether they’re of persecution, ambition, grief or terror. Hurrell has made firm, unusual and interesting decisions as a director, and committed himself and his cast to them absolutely.

THE ANGLE

Macbeth

Nicholas Eadie

Lady Macbeth

Margot Fenley

Young Siward

Jonathan Ford

Duncan / Old Man / Siward

John Gregg

Ross

Doug Hansell

Banquo / Menteith / Messenger

Peter Hayes

Donalbain/Seyton

Matt Hyde

Lady Macduff / Porter / Gentlewoman

Danielle King

Macduff

Ashley Lyons

Malcolm

Paul-William Mawhinney

Angus/Murderer

Adam McGurk

Sergeant

Woody Naismith

Lennox/Doctor

John Turnbull

Young Macduff

Andrew Brophy or Lawson Tanner

Fleance

Mitchell Burge or James Fraser

Lighting And Sound Operator

Victor Areces

Stage Manager

Eilza Ocana

Rehearsal Room Stage Manager

Katharine Rogers

Set Construction

Go-Mez Constructions

Production Crew

Karina McKenzie & Danielle Bertozzo

Director

Christopher Hurrell

Movement Director

Mackenzie Scott

Assistant Director

Lincoln Hall

Set Designer

Justin Nardella

Costume Designers

Michael Hankin & Lucilla Smith

Lighting Designer

Stephen Hawker

Sound Designer

Steve Toulmin

Producer

Anna Sampson

Production Manager

Phil Berry

Photography

Tom Evangelidis

I assume that the play, with its witches and demons, spells and visions, was originally designed by Shakespeare to terrify a superstitious audience. That’s something which is lost from the play’s story-telling now and I began by wondering if it’s still possible for the play to be terrifying on stage. We are more likely to find stage-witches funny than frightening. However, what remains terrifying about the witches, is that their presence in the play suggests the possibility that we can’t control our own destiny. What’s terrifying about Macbeth is that we relate to him so keenly, even as he descends into violent horror.

I concluded that I wanted to do the play without magic and spells and potions and cauldrons, but NOT without the presence of the witches. I noticed that the things they say were much more appalling and horrifying when I was able to merely listen to the images conjured in the text – without reducing those images by literal representation. Also I realized that one of the things I love about the witches on the page, is that their presence has mystery and ambiguity. A very common question when studying the play at school is “how real are the witches?” Productions of the play seldom find a way for this doubt to live, despite the fact that both Banquo and Macbeth express doubts in the evidence of their own senses. So I decided to ‘disappear’ the witches into the ensemble by sharing their roles amongst most of the members of the company.

I wanted to offer some provocations to unsettle the over-simplified way in which we are introduced to this play as teenagers at school:

- That rather than combining the heroic and villainous character types into one man –Shakespeare has disbursed them in varying measure amongst all the inhabitants of the world of the play.

- That the play is actually very little to do with ambition. It’s NOT merely a more sophisticated version of Richard III. A recent quote from Declan Donellan put this into sharp relief for me, when he said “I always thought the play was about a husband and a wife deciding to kill a king. But actually it’s a play about a husband and wife REALISING that they HAVE killed a king.” I think the temptation that draws them is far richer and darker than simple ambition for power. The seed is planted by a force, represented by the witches, that is far more primal and visceral than that. Macbeth is seduced more by his uncontrollable and dark imagination than by practical ambition.

- That the source of Macbeth’s capacity for monstrous action is locked inside the brokenness of his own soul. In the pre-psychoanalysis world of the play this is explored through recourse to the spirit world, via the witches and via Lady Macbeth’s searching and Macbeth’s imagining.I want to break open that representation. A world ‘ beyond’ human flesh, is also a world ‘within’ it.

- That the play doesn’t have a natural journey from a disruption to a restoration of natural order.The play inhabits a dis-ordered world, already subject to an infestation of evil spirits and violent rebellion. And ends still out of balance. With the witches’ prophecies yet to be fully enacted. There is at least one more violent upheaval to come in the future, before a natural , divine and hereditary line of Kings (of which the first will be Fleance) will bring political order.

I want to create a theatrical world for the production that ‘exposes’ character – where psyche and soul are unprotected. To me, the world most richly illustrated in the poetry is not pre-modern Scotland, or a martial society, or even a land where ‘dark arts’ run rampant, its the world of the Macbeths’ imaginations, dreams and nightmares. Those imaginings, dreams and nightmares are largely created by the Macbeths but they do not solely belong to the Macbeths. The most memorable text for all of the major characters and many of the cameos, is when they engage their imaginations in horror. In this sense the whole play and most of the characters are haunted I think.

What’s important about the physical world of the play is that because of era, terrain, weather and warfare, it’s a world where the physical body is highly vulnerable and under extreme duress. So for example we used no weapons in the production, freeing the body from safety concerns to be able to engage creatively with the physical expression of what happens to frail human flesh when it comes violently into contact with mediaeval armoury.

We worked extensively with a movement director, to create an ensemble performance of physical rawness and extremity. It was a production where the whole ensemble worked on stage for most of the show. This shared physical work expressed the essence of mood, time and location, with the barest minimum of carefully deployed suggestion in costume, scenic and props. I wanted the audience’s imagination to be as active as Macbeth’s is.

Review in Australian Stage by Brett Casben

This production currently performing at the ‘Darlo’ in Sydney, directed by Christopher Hurrell, is an adventurous production in several ways.

First and foremost the program motif; the lead couple, Nicholas Eadie and Margot Fenley hands clasped and blood seeping from their palms. It may not quite ‘say it all’ but the message would seem to be ‘blood brothers’ or whatever the extension is, ‘blood siblings’. It’s astute, pointed and accurate. It’s also deliberate. This play is about incest. It’s not stated directly in the introductory scenes as is common with other Shakespearean works because it is the ‘lover that dare not speak its name’.

Hurrell refers in his notes to ‘instinctively longing to see’ the pair as the Thane and his spouse when working with them on a production concerning corruption. This really should not come as a surprise because while Shakespeare’s stature as a poet and dramatist is universally acknowledged his role as propagandist is not always well recognized. He was introduced to the revived art of ‘Greek’ posie as a socio political talisman by the young Chistopher Marlow. After Marlow’s death Shakespeare took on his mantle. His works, as political satires are therefore played out on two levels, the apparent story for entertainment and the referenced incidents or allegory for edification. The allegory is not ‘subtext’ it is the principle story of the play. It’s what has evolved into propaganda.

One of the most refreshing aspects of this production is the humour. It is not usual to associate this blood curdling bleak tale of regicide with humour however it can be quite funny when the audience is acquainted with the play’s antecedents. As Hurrell points out in his notes it’s a good deal more complex than a story of ‘ambition and lust for power’.

The underlying allegory has been obscured by the heavy censorship this work was apparently subjected to after Shakespeare’s death. As Granville-Barker suggests ‘when it came to printing the Folio the manuscript of the first four scenes had vanished … what we have left is the result of the mobilizing of memories of actors and prompter. Some lines they recalled accurately, some lines they confused and some they had forgotten altogether.’ We are also now a long way from what was being played out in the corridors of power to which the play referred.

The opening of the play is muddled but to overcome this Hurrell has collapsed the scenes and disbursed the lines among the cast who are all present on stage. The result is a ‘spell binding’ chant,

A sailor’s wife had chestnuts in her lap,

And munch’d, and munch’d, and munch’d:–

‘Give me,’ quoth I:

‘Aroint thee, witch!’ the rump-fed ronyon cries.

Her husband’s to Aleppo gone, master o’ the Tiger:

It wasn’t intended to frighten anyone, in the sixteenth century or the present. It’s purely a piece of bawdy, the joke that breaks the ice. The referent of ‘chestnuts in her lap’ being the distinctive physical characteristic of hair colour that was shared by another Queen and those of the house of her Lord Chamberlain, Elizabeth I and Henry, Lord Hunsdon. It’s a trait presumably acquired from Henry VIII through the Boleyn girls who between them produced both blood lines. It becomes apparent why there was such heavy censorship of the opening of this work as opposed to many of Shakespeare’s other works.

Macbeth was presented by Shakespeare at an extremely vulnerable time for him. James I had just come on to the English throne with a new administration. His right of kingship harked back to before Henry VIII. The role Shakespeare had carved out for himself with Elizabeth under Lord Hunsdon’s patronage made him a prime target for early ‘retirement’. Macbeth then was an apology or justification presented to the new monarch as a pledge of honour.

Michael Hankin and Lucilla Smith have devised an archetype costume in shadowy grays that avoid dating but convey a stark bleakness. The barefoot cast afford an interesting opportunity for Hurrell to dabble in another piece of symbolism, ‘crowning’ the couple later by putting shoes on their feet, so marking it as an upside down story.

Macbeth is an upside down allegory, presenting symmetry between the apparent story and its allegorical counterpart. Like England and Scotland you turn it upside down to get the opposing perspectives. For Scotland read England and vice versa. In the original production young men would have taken the female roles. The practice has sometimes been said to result from a social bar on women on stage. It is a device, however, that gives more flexibly in allegorical construction by removing inherent sexuality which might invest the allegory in unintended ways. At the time it was written the terms ‘king’ and ‘queen’ were not gender specific, they were analogous to their use in chess. The king was restrained by political convention whereas the queen was flexible in the initiatives undertaken.

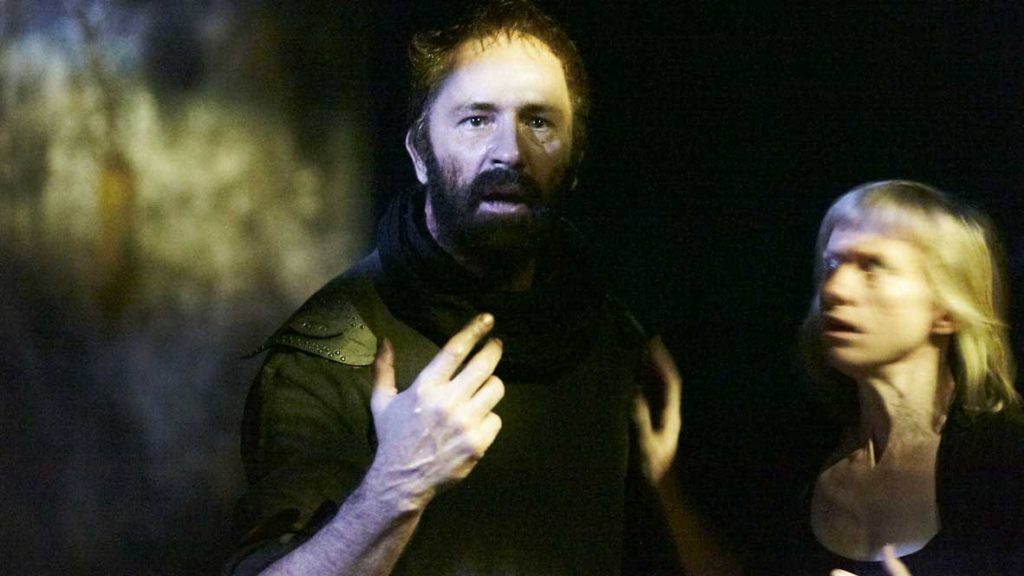

James I frequently refers in memoranda to his Lord Chamberlain as his ‘queen’ after some divergence from his Consort, Anne of Denmark, so much so that Victorian historians determined he was homosexual. Likewise Hunsdon was ‘queen’ to Elizabeth’s ‘king’. When viewing pictures of Hunsdon and those of Elizabeth, it’s easy to see why Hurrell longed to see Eadie and Fenley in the roles. Eadie presents a formidable physicality that is both heavy and agile. He is a man at once urgent in action but ambiguous in responsibility. Fenley, on the other hand presents as slim, taut and feisty. The physical reversal in the characters seen in this production succeeds in making this duality both convincing and complete. They aren’t exactly ‘chestnuts’ but that’s presumably why the verse is there.

The humour is pretty dark but apparently so was the taste of James I. One of the repeated gags is in the use of the rhyming couplets. They tag some of the bleakest moments in the play giving a strong melodramatic spin.

The inherent humour in the work could hardly be missed when Danielle King gets woken up as the Porter. That may be very pointed but Hurrell doesn’t shy away from it wherever it crops up even when the precise referent is no longer well understood.

Hurrell invests this production with a rigorous forward movement in order to maintain tension by removing what have always been rather arbitrary scene and act divisions. By insinuating the cast of the incoming scenes into the current one he eliminates the need for scene changes. The only interruption to the dramatic thrust of the play which is fast and furious, is where the text demands a change in mood.

The ‘acting‘ areas which demarcate the space rely heavily on a simple yet effective ploy of moving chairs with accompanying light transfers. Lighting for space and mood was devised by Stephen Hawker.

Justin Nardella’s staging has pared the scenery and props down to the barest minimum, relying almost entirely on the illusionary scenery provided in the text. This also makes a major contribution to carrying the action forward. The stark chaotic backdrop is pointed up as identifying the ‘state of play’ when Duncan, played with a certain weightiness by John Gregg, faces the bleak outlook to comment, ‘This castle has a pleasant seat’. The allegorical referent presumably was Whitehall which, by all accounts, was anything but. Even the sword fights are cleverly choreographed illusions, courtesy of movement director, Mackenzie Scott.

Possibly the most notable achievement is in what is dubbed the ‘ensemble’ work. The group was brought together for the purpose of the production and is not an ensemble as such. Nevertheless Hurrell has managed to evoke a wonderfully balanced homogeneity within the cast. In a very positive move he encouraged the cast to evolve the play’s structure themselves even to the point of having the lead actors present at later casting calls. He acted as facilitator.

Because of the omissions in the opening scenes the dual allegory of Macbeth remains one of conjecture. It seems however to pick up Elizabeth’s reign at the time of the Northern rebellion which involved Lords Norfolk, Westmorland and Northumberland represented in the play by Duncan, Malcolm and Macduff.

The plot of Macbeth, for the sake of those who are not familiar with it is simple enough. Set in Scotland in the eleventh century, a prominent lord, Macbeth, having acquitted himself bravely in defence of the King in a rebellion by the lord of Cawdor, is elevated to that title. This places him within striking distance of the throne. Macbeth’s wife encourages her husband to murder the king and so preemptively gain the crown. Thereafter several intrigues shore up his authority but ultimately their crimes eat away at them from within. The Queen commits suicide. Macbeth is then killed in single combat and the rightful heir is placed upon the throne. Through all this there is the undertone of the fates and of witchcraft, a particularly favoured topic of James I.

All these machinations explore the strange relationship that led the monarch and her Lord Chamberlain on a course of bloody retribution to preserve the Protestant crown. Following Elizabeth’s accession she was constantly under threat of Catholic insurrection through her northern neighbour. It is possible that Ross, played by Douglas Hansell is the playwright himself and the English doctor, played by John Turnbull, might represents Lord Cecil.

In the pivotal roles of Macduff, played by Ashley Lyons and Malcolm, played by Paul-William Mawhinney, Hurrell has achieved the essential contrast between them: the stormy and impetuous Macduff and the calculating, diplomatic Malcolm. They may find their reflections in Thomas Percy and Charles Neville. Lyons is particularly noteworthy for a portrayal of a man at first wary of being inveigled into his cousin’s schemes. When confronted by his own wife’s and children’s murder, however, he becomes a man possessed. With nothing to lose there is nothing to hold him.

Danielle King gives a moving interpretation of Lady Macduff in a scene shared with the young Macduff, on this night played by Lawson Tanner. On this occasion King braved the embargo on playing opposite children and animals and despite Tanner’s very accomplished interpretation acquitted herself and her generation with great style. Both actors delivered a wonderfully understated repartee that was warm, amusing, endearing, frightening and courageous; the quintessential doublet.

This company was admirably complemented by strong performances by Andrew Brophy, young Macduff (alternating with Tanner), Jonathan Ford, young Siward, James Fraser as Fleance, Peter Hayes as Banquo/Menteith, Matt Hyde, Donalbain/Seyton, Adam McGurk as Angus/murderer, Woody Naismith, sergeant.

For those who may be interested in the historical summation of events; in the closing stages of Hunsden’s life for whatever reason Elizabeth distanced herself from him and in one of his last letters to Burghley, he complained:

‘her Majestic ys so reddy apon so small cawse too deale thus (nott hardly) but extremely with me, as I hade the offyce of Barwyke of her Majestic specyally, and only by your L. goode meanes agenste the wylls of uthers … an offyce of that charge ys not to be govern’d by any, that hath no better credytt or countenance of hyr Majestie’s then I have ; for I am nott ignorent, what qwarrels may be pykt too any mane, that hathe such a charge, if the Prynce shall be reddy, nott only too heare every complaynte, whyther ytt be false or trew ; and so apon imagynacion too, condemn without cause.…

At Hunsdon this 8 of June 1584

It could almost have been the words of Lady Macbeth. On his deathbed Elizabeth offered to create him Earl of Wiltshire but he refused,

‘Madam, as you did not count me worthy of this honour in life, then I shall account myself not worthy of it in death’.

Macbeth is, as often stated, the apology of a dramatist seeking to ingratiate himself with a new administration however it is far more than that. It is also an apology on behalf of two people he loved and served for a great many years. It is a great love story, a love between two people who happened to share parents whose common blood forbad their public avowal. At such a level of political and social rarefication who are we to judge?

History shows that the play served its purpose. James I issued fresh patents in favour of Shakespeare’s players thenceforth called The King’s Players and James himself became their patron. Will could hardly have hoped for a more glorious outcome. Perhaps the couple he had served so well as the ‘conscience of the king’ had not been too harshly judged after all. Perhaps in some strange way they, too, had been vindicated by this passionate plea on their behalf.

It is a wonderful play and a memorable production that shows both insight and courage.